Ep 17: A true artist: Jiang Kui

“The aim of every artist is to arrest motion, which is life, by artificial means and hold it fixed so that a hundred years later, when a stranger looks at it, it moves again since it is life.” ~William Faulkner

What values do Jiang Kui and his creative works bring to the world? Jiang Kui (A.D. 1155-1221), a famed poet of China’s Southern Song dynasty (1127-1279), played a significant role in Chinese musical history. He was among a few literati who were known to have actively participated in the composition, realization, performance, and notation of ci music.[1] Pieces attributed to him, collectively known as Jiang Kui’s Collection of Songs of the Whitestone Daoist, which survive today in written form, are among the few known examples prior to the Qing dynasty where we have ci combined with music.

In his study of Jiang Kui, Professor Joseph Lam points out that there is desperate need for a comprehensive understanding of Jiang Kui’s music and nuanced narratives to explain his life and works. Born as an orphan, Jiang Kui grew up with the support from patrons who appreciated him as a talented musician, poet and calligraphy. Even though all his life he was a destitute artist who could hardly afford to explore the vigorous aspect of his life, he nevertheless shines through his art till today. [2]

Jiang kui not only left us a considerable amount of shi and ci poems, a decipherable notated tunes in Chinese music history, but also theories of calligraphy, poetry and music.[3] He is most famous for a remarkable series of seventeen ci lyrics with accompanying music he composed as they are a valuable source for the study of Song-dynasty music and musical notation. The richness of his output in writing is unmatched by any other of his day. As a real artist, he dipped his brush in his own soul, he wrote and acted as what he believed. Even though Jiang Kui was not included in the standard history of the Northern and Southern Song dynasties, Songshi, because he was politically driven as most of his contemporaries were, his stories should be told in nuances as they will continue to enlighten artists today.

I will start with my paper with a close reading of Jiang Kui’s most famous work Anxiang in light of his autobiography to show how Jiang Kui was able to capture and recreates his life in poem, music and calligraphy out of his own experience and understanding of life. Jiang kui gave up pursuing a path of political fame and became a Daoist when he realized his passion in seeking the best way to combine literature and music in writing ci. At a time when “Musician” was a role that carried distinctive and usually undesirable connotations among the Chinese literati, Jiang Kui was courageous in becoming one of the few known composers of the Song period. As professor Rulan Piao notes “His fondness for experimenting with theoretical modes and his interest in recovering old forgotten music show that his approach to music was an intellectual one.”[4] Jiang Kui remained a musical literati, and continued throughout his life to pursue his intellectual and practical interest in historical music, even though he could barely afford himself a living on selling his calligraphy.

Jiang Kui believed that music itself does not contain any emotion, and the composition and performance of the piece are what fills the music with meaning beyond what simple notation can encompass.[5] Therefore, he not only devoted himself in writing innovative ci, but also preserving a notation system that encourages creativity in ci writers. Thanks to Jiang Kui, an important notation system was preserved as part of Chinese cultural heritage that opens a door to the study of Song dynasty music.

What distinguished Jiang Kui is his invaluable traits as a true artist. Unlike his fellow scholar-theorists, he showed no hesitation to cross social boundaries and learn from the lower-class professional musicians.[6] Jiang Kui also once "petitioned to the Royal court of the Southern Song dynasty to regulate the musical tones for rituals, and made a list with analyses of theories on different ways to tune the guqin."[7]I will present my study of Jiang Kui’s ci Guyuan, which is included in Jiang Kui’s collection Songs of the Whitestone Daoist, a work written and published in the middle of the Southern Song dynasty. It is not just the earliest publication of a qin melody to survive, but also part of China’s unique cultural identity that is irreplaceable by anything else.[8]

Jiang Kui was highly valued for his artistic achievements, judging by the status of his patrons and the level of talent among his close friends.[9] The most intensive study of Jiang Kui’s life and works started in the mid-eighteenth century in China, when a new printing of his poetry and notated music came out. Since then, a scholarly tradition of Jiang Kui studies has developed. Throughout the centuries, Jiang Kui and his works have become a regular topic in Chinese discussions of literature and music.[10] As an artist from Song dynasty, Jiang kui has much to offer on the meaning of a true artist that reckons even till today.

The following poem Anxiang is written by Jiang Kui using an old tune he found, after Jiang Kui learned that the woman he was in love with had gotten married. Jiang Kui was loyal to musical and poetic composition, just as he was loyal to the one woman he loved. When Jiang was around twenty years old, he lived in Hefei, where one day he ran into a pair of singing girls who were performing Pipa in the entertainment district. He immediately fell in love with one of them, but as he was poor all his life and had to travel in search of patrons, they did not see each other again. For this, he had his share of personal regrets. However, he wrote about his love for her in twenty two poems, almost one fourth of the pieces he composed his whole life. As the editor of Jiang Baishi ci bian nian jian jiao Professor Xia Chengtao noted, Jiang Kui’s ci about love is the most prominent of all ci written in the Tang and Song dynasties.

Jiang Kui rarely expresses his feelings of love explicitly in his poems, and the emotion is always concealed between the lines, as his song lyrics often exhibit a difficult and obscure style. In fact, the interpretations of this poem range from a reminiscence of the girl he loved, an expression of outrage for the capture of the last two Northern Song emperors, to an expression of sadness for his life as an unemployed scholar-artist. Jiang Kui is an important poet, but people’s understanding of him as a poet was deeply affected by the literati culture of the Song dynasty.

Professor Stephen Owen, an American Sinologist specializing in Chinese literature who teaches East Asian Languages and Civilizations at Harvard, wrote in his book An Anthology of Chinese Literature that “Jiang Kui represents a new type of literary figure that appeared in the Southern Song: the more or less professional writer-musician who lived as a client of the rich and powerful. Jiang Kui never served in public office, nor did it seem that he had any inclination to do so. He was, above all, a craftsman who sought the perfect union of word and melody.”[11] Indeed, even though there is still mystery surrounding the artist on questions like how he learnt his music and his choices on composing ci tunes, this idiosyncratic artist provides us data that decodes the relationship between music and poetry. In evaluating his famous poem Anxiang with Professor Owen’s translation, I intend to show how knowledge of his life, Song dynasty music and calligraphy change the way we read his poem as a unique form of art.

As the translation “song lyric” suggests, ci are verses in irregular line-lengths that are written—or, literally “filled in”—so they could be sung to existing melodies. Compared with Tang poetry, ci is more closely related to music. In theory, there exists poetry that cannot be matched with music, but there is no ci that does not take music into account. There was a long history in the development of ci before it became the custom to write numerous lyrics to fit a single tune, so that in time a number of fixed metrical patterns were established, each known by the name of the tune it fit. There are many different ci tunes and each of them has its own requirements. The requirement includes number of lines, how many words in each line, and how every sentence has designated tonal patterns and rhyming.

For example, one ci tune’s name is “Qing Pingle” and for every ci composed with this tune, it needs to follow these requirements: eight sentences divided into two stanzas and each sentence structured with four words, five words, seven or six, six or six, six or six (words). The first stanza follows a specific phonology, and the second following another. What about composing a ci first and then fill the music in? It is not common, but masters of composing are able to compose “Zi duqu”, which are new ci tunes (music). Anxiang is one of them.

“First music, then poetry” allowed music to determine the shape of poems. In the song lyric, poetry and music became truly unified arts. The songwriter is free to express his ideas and experiences with more complexity and without the restriction of the rigid, regular, and balanced rhythm of recent-style verse in Tang poems.

Jiang kui invented the new ci tune named Anxiang and composed the music after he wrote the ci. In composing, the most important factor in a ci tune is the music, and the major rule of composing a “Zi duqu” is to write in the ci based on the music tune. Each ci tune is actually a song with a fixed rhythm, and one can fill in different ci, but the rhythm stays the same. In composing a ci, one needs to take into account the four tones of classical Chinese poetry and dialectology, which are the four traditional tone classes of Chinese words. They are named even or level (平 píng), rising (上 shǎng), departing (or going; 去 qù), and entering or checked (入 rù). The tonal pattern of ci needs to match with the music tune so it could be sang. Anxiang strictly follows the rule of composing.

Owen’s translation:

In the winter of 1191, I went off in the snow to visit Fan Cheng-da at Stone Lake. When I had stayed with him a month, he handed me some paper and asked for some lines to appear in a new style song. I composed these two melodies. Fan Cheng-da couldn’t get over his pleasure in them, and had a pair of singing girls practice them until the tones and the rhythms were sweet and smooth. Then I gave it the name “Fragrance from Somewhere Unseen”.

The moon’s hue of days gone by--

I wonder how often it shone on me

Playing my flute beside the plums?

It called awake beside that woman, white marble,

And heedless of cold,

Together we snapped off sprays,

But now this poet grows old,

And the pen that once wrote songs

Of the breeze in spring

Is utterly forgotten;

I’m just intrigued by those sparse blooms

Over beyond the bamboo,

How their chill scent

Seeps into party mats.

These river lands now

Lie somber and still.

And I sigh

To send them to someone traveling far,

As tonight their snow begins to heap high.

With kingfisher cups

And easily brought to tears,

Restive, I recall

Pink petals that never speak.

I always think back where we once held hands:

Where the freight of a thousand trees weighed

On West Lake’s cold sapphire.

Now petal by petal once more

They all blow away

Never again to be seen.

The preface particularized and authenticated Jiang Kui's individual existence and artistry. As argued by Shuen-fu Lin, the artist used the preface to "create a separate artistic entity within the larger totality of the preface-cum-song: the preface not only indicates the origin and content of the songs but also give "a realistic context or a frame of realistic reference" to understand what the song is "intended to mean."[12] During his life, Jiang Kui wrote not only ci poems but also tunes. Not only aiming to preserve traditional tunes[13], he also composed a number of new tunes, which he labeled as his "own compositions" (Zi duqu). As Professor Shuen-fu Lin noted, “the long relationship between Chinese poetry and music resides in the particular characteristics of the music to which the lyric was set.”[14] Jiang Kui’s attempts to use the distinctive features of the Chinese language to create a kind of music in poetry achieved what has been called the “musicalization” of poetry by Chinese literary historians.[15]

Temporality is indicated in the first half of the poem, which begins with “the moon’s hue of days gone by,” which is indicating that the poet is deep in his memory of the past. These memories have brought him sadness, and the coldness of the spring night emphasizes his melancholy that the woman with whom he “snapped off sprays” in the sixth line in the past is now gone. “That woman, white marble” in the fourth line should be translated literally as “jade lady”, a phrase that appears in many poems throughout Chinese literary tradition, and it often is a symbol of goodness, preciousness and beauty. To refer a lady as having the character of jade means she is the embodiment of virtues such as courage, wisdom, and modesty. The Chinese saying that "Gold has a value; jade is invaluable" indicates that Jiang Kui is thinking of the Jade Lady that he was with, but she is no longer by his side.

Jiang Kui pays special attention to how different tunes have different requirements for emotional expression. The melody of the music is soft and clear, so he composed ci with the theme of romance. He begins the second stanza with “But now this poet grows old,” which in the original is “He Xun is now old.” He Xun was a poet from the six dynasties who wrote poems about spring winds and plum blossoms.[16] Here he borrowed the setting from He Xun and made it his own. In fact, he not only borrowed the plum scene in He’s poems, but also the meaning behind the scene to convey his emotions. He Xun was famous for depicting scenes of departure, and here Jiang Kui expresses his feelings through his poem in an attempt to convey his sadness at becoming old. While he did not want to be “intrigued by those sparse blooms”, he was saddened by the memory the plum blossom evoked. In considering Jiang Kui’s ci, we must draw upon what we know of his emotional nature, and keep in mind that there is often the scene perceived by the poet and the scene perceived by the reader. Reading poems in light of items of the poet’s personal history is challenging, but often a necessity in understanding song lyrics.

As the first half of the poem centers around the poet’s love for cherry blossoms, the second half moves to examine the theme of love for his country. As the poet was writing the poem, Song dynasty was deep in war, and the desolation the country was experiencing is reflected in the poem. The first stanza of second half starts with a depiction of the river lands, which are in the southern part of Hangzhou, where the northern Song’s capital resettled after the Jurchen’s invasion. What are the river lands like? As grass and flowers just start to grow in the early spring season, the snow then starts to pile up, as if taking away the hope and positivity left of the season, and the country. Some scholars argue that the river lands he referred to could likely reside in his own imagination, but regardless of where the river lands are, real or imagined, the feeling of desperation is prevalent in these lines.

The poet’s loneliness makes him feel like “their snow begins to heap high”, and that even the “kingfisher cups” are saddened by the poet’s despair.[17] As the poet’s mind drifts through memory back to the time he was seeing the pink petals of cherry blossoms, he remember the “pink petals that never speak”. The petals are silent, and the poet is speechless as well, but somehow the power of silence is stronger than thousands of words. While there is a strong internal emotion, the sound did not take shape, it only gained its power when readers contemplate the meaning of this silence, and then it is internalized as a kind of consciousness. Using simple language, Jiang Kui created a vision of the world that was uniquely his. As the poems draws to the end, the poet starts to reveal his thinking. As he writes “I always think back where we once held hands: Where the freight of a thousand trees weighed / On West Lake’s cold sapphire.” This line is a beautiful translation from word to image. He is expressing his longing to go back to the day when cherry blossoms and the lady he loves were both by his side, and the country was prosperous, full of energy and hope. When can I see her again? The poet seems to ask. But life only goes forward, and as the petals starts to fall, the poet realizes he cannot go back in time.

Jiang Kui has the ability to cross from the dimension of sense to that of the mind. In the stillness of nature, his artistic process in weaving together the sense and the mind in an attempt to express his real emotion, is presented by the excellent use of historical metaphors like “He Xun has gone old”. The cold moonlight from the first stanza continues into the second stanza and turns into the light of snow covered river country, and reader immediately understands the emotion behind the change. In the verses built up from a mixture of long and short rhythmic units with distinct curves and turns. In Jiang Kui’s ci, poetry and music became truly parallel and unified arts, and he could express his ideas and experiences in a more complex process and the music of the song lyric is itself a structure of feeling as well.

As we take into account the events of his personal life during the short period when he was writing this, we see more implications behind his poem. The author wrote with nostalgia, at a time when the country was already partially conquered by outsiders. One year before the poem was written, in 1190, he lived in a place near the White Stone Cave in Wuxing County. Because of that residence his close friend Fan Chengda, whom he wrote this poem to, gave him a distinctive style name—White Stone Daoist, alluding to a legendary Daoist immortal who reputedly retired to a place called White Stone Mountain and lived on a diet of boiled white stones. Jiang Kui adopted the name as a suggestion that he had adopted the Daoist way of living in nature, and had given up the Confucian goal of becoming an official. His life is to be read as having influenced his poetry and contributes yet another element to the emotional background that we cannot ignore. Jiang Kui never succeeded in obtaining a government post. He supported himself by selling his calligraphy and received substantial financial aid from wealthy friends and patrons. Even though he adopted the way of Daoist life, he continued to be active and creative as a poet, musician, composer, calligrapher, and theorist of poetry, music, and calligraphy.

Jiang kui not only left extensive works including poems and prose pieces, he was also famous for Xu Shupu (sequel to the Treatise on Calligraphy), as well as an important work on poetics entitled Shi Shuo (Discourse on Poetry). In his theory of calligraphy, he expresses what he believed to be the spirit of not only calligraphy, but also life.

In the section of “bearing” in Xu Shupu, Jiang wrote “The first requirement for the bearing [of the characters] is a noble character [on the part of the calligrapher]; the second is modeling oneself on ancient masters; the third is good-quality brush and paper…the seventh is a suitable internal balance; the eighth is occasional originality. When these requirements are met, long characters will look like neat gentlemen…” Jiang Kui is a man who not only has an extraordinary talent in music, poetry and calligraphy, but also a personal with integrity. [18] He could have chosen to pursue politics, but he decided to remain a real artist who though he lived most of his life as “a wandering and destitute artist”, Jiang Kui was keen on offering later generations a chance to know who he was and what he could offer. [19] He wrote detailed prefaces to a number of his poems and music, revealing insights about himself, his works, and his musical life. He put much effort into writing and preserving notation of music to ci poems, so we can know how song lyrics were actually sung, outside of the ci itself. Tz’u is difficult to sing, and most of the tunes of the tz’u were lost long ago, but thanks to Jiang Kui who notated most of his tz’u, scholars can now study such areas as the musicalization of poetry.

Only two musical works dated before the Song dynasty still exist today, and even though people have found important musical documents throughout the entire Song period, for more than a century shortly after Song, for some reason, no music of any kind survives.[20]Therefore Jiang Kui’s notations of Guyuan offered a really invaluable chance for scholars to study music in the Song dynasty, and also for later generations to express their individuality through the process of dapu.

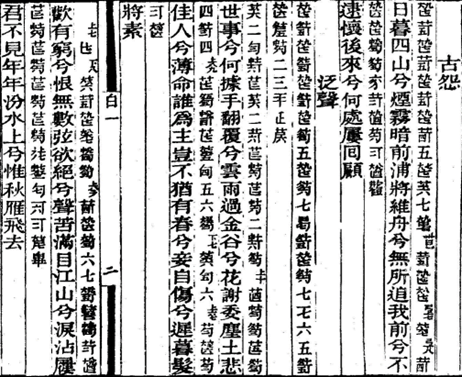

The full title of Guyuan is usually given as Baishi Daoren Gequ Gu Yuan (Ancient Lament, from Songs of the Whitestone Daoist, 1202 CE).[21] Guyuan is the earliest ci written with Jianzipu, and it has become one of the most valuable documents in studying music in the Song dynasty. The songs by Jiang Kui, with both the text and music preserved, reveal some interesting principles behind musical composition of his time.[22]

Jianzipu (“abbreviated graph notation”) is the standard traditional Qin notation system, which resembles ordinary Chinese writing. The Qin notation is holistic, attempting to achieve a single, integrated definition of a sound within a single, integrated “graph”. Different from what is normally expected of a musical notation system, Jianzipu describes how the sound should be made (fingering, the hand position, the nature of the strum, etc.) instead of the sound itself (i.e. duration, pitch, tune). The core of each graph is called a “Jianzi” (a single abbreviated character), which by itself can indicate many meanings.[23] In the piece Guyuan we can see how the numbers indicate the technique, whether it is ‘thumb pushes string six’ or ‘middle finger pulls string one’.

The process of transforming a piece of music from score to sound, called dapu in Chinese, exemplifies how the notation encourages the performer's’ creativity through composition and practice. The performer first learns the music by heart and then explores the deeper meaning and uses training and sensitivity to interpret the score based on everything that is provided. In this way, a player’s individual artistic creativity is greatly encouraged, since the Jianzipu can act only as a guide, and detailed handling of the music like the exact pitch and duration are at the discretion of the qin player. When musicians start to dapu, they must first read the tablature symbols correctly, researching the meaning of the symbols at the time the score was written so they can land on the correct mood and appropriate musical color.

Dapu cannot be directly equalized with the Western concept of improvisation, though spontaneity and individuality were indeed greatly treasured in qin composition. Qin’s notation gives the bare bones of a piece of music but requires the performer’s further interpretation. More importantly, the music is somewhat defined by the performer's’ interpretation. Unlike western staff notation, Jianzipu functions less as an authoritative notation but more as a blueprint and a means of keeping a record of the original music notation. This distinct notation that Jiang Kui helped to preserve affects composition and performance practice in many ways, from the moment it was created until this day.

Image: Guyuan’s complete original tablature

It may come as a surprise that Jiang Kui is not as well received by later generations as he should be, taking into account his contribution to the musical history of China. In fact, he is only remembered by the Songshi[24] for ten state-related songs.[25] The partiality of the Songshi representation of the artist is apparent: it does not mention his ci songs, the focus of modern interest. The focus with the Songshi was not impartial, as we have already seen, itself being a reaction to the Confucian view of music and musicians. Nowadays, instead of Confucian perspectives on music and musicians, art subscribes itself to the socialist perspectives of Mainland China.

Under the influence of nationalist sentiments in the early 1920s, Chinese universities incorporated some Western music courses. Under the larger social influence in which the Chinese view modernization as the retention of Chinese essence through Western means, musicians at the time began to think and hear music in terms of Western intonation, harmony, tone color, range, and above all, standardization of music. Ancient Chinese notation systems like Jianzipu were replaced by western systems. Later during the 20th century under Mao’s leadership, Chinese artists were under pressure to produce “politically correct” art with ideological messages. For more than half a century, the fundamental function of all art forms is to state or restate the political goals of the party and the nation. It was also the time when the most catastrophic event for Chinese culture happened: The Great Cultural Revolution demolished all sorts of antiquities as symbols of "old thinking." Priceless historical and religious texts also were burned to ashes.

Even till today, art is under censorship in mainland China, and it would be truly hard to find someone like Jiang kui today, who is courageous to express his real emotion through art, challenge the authority, and fight to preserve cultural heritage. William Faulkner writes that “The aim of every artist is to arrest motion, which is life, by artificial means and hold it fixed so that a hundred years later, when a stranger looks at it, it moves again since it is life.” We are really lucky to have Jiang kui who helped preserve the “voices” of ci. His ci pieces, which were sung to music that, even after its disappearance, left a powerful legacy in terms of the shape and contexts of the genre. Even when he very poor, Jiang kui captured his life experience through poetry and calligraphy, and used music as a core form of expression, so later generation could perceive what life was like for a unique musician like him in Song dynasty. If we think for a moment not about the literary qualities of his ci or the music he produced, but about the biographical and historiographical interest they hold, we perceive at once Jiang kui was a rare and valuable artist he is in this regard.

[1] Lam, Joseph S. C.. “Writing Music Biographies of Historical East Asian Musicians: The Case of Jiang Kui (A.D. 1155-1221)”. The World of Music 43.1 (2001): 74.

[2] Lam, 75.

[3] Lam, 76.

[4] Piao, 45.

[5] Chengtao Xia. Jiang Baishi ci bian nian jian jiao, Shanghai : Shanghai gu ji chu ban she. 1958.

[6] Lam, 79.

[7] Hsu Wen-Ying, The Ku-ch'in, 327.

[8] Covered with layers of lacquer, qin is a seven-string, fretless, plucked long zither that has a shallow and oblong resonator. This ancient and amazing instrument was favored by scholars and literati as an instrument of great subtlety and refinement and has been witnessing its own revival in recent years.

[9] In his life, Jiang Kui never achieved important office, but made a living selling his calligraphy and getting patronage from wealthy friends. He was good friends with many famous poets of the time, such as Fan Chengda.

[10] “Study of Jiang Kui still thrives: nowadays days, many scholars working inside and outside Mainland China are continuing the tradition, producing detailed and sophisticated studies” (Lam, 70-72).

[11] Owen, 585

[12] Lam, 90.

[13] When he found old tunes, he would set them to new ci lyrics.

[14] Lin, Shuen-fu. "The Formation of a Distinct Generic Identity for Tz'u." Voices of the Song Lyric in China. Berkeley: University of California, 1994. 12.

[15] Lin, Shuen-fu. "The Formation of a Distinct Generic Identity for Tz'u." Voices of the Song Lyric in China. Berkeley: University of California, 1994. 8.

[16] He Xun wrote many poems on plum blossom, the most famous one being the poem on spring wind which is presented as follows:

《咏春风诗》:“可闻不可见,能重复能轻。镜前飘落粉,琴上响余声。”又有《咏早梅诗》:“街道当路发,映雪拟寒开。”“应知早飘落,故逐上春来。”

[17] Poem and which line

[18] Pian, 27.

[19] Lam, 90.

[20] Politically, the three centuries of the Song are isolated by a preceding fifty years of anarchy and a hundred years of subsequent foreign domination, but there is as yet no basis for the periodization of Chinese music. Piao, Preface.

[21] “The Bairshyr Dauren Gecheu is the most famous of all musical sources from the Song dynasty…. This collection contains Jiang Kwei’s poems, twenty-eight of which have musical settings, twenty-three composed by the poet himself.” Pian, 33.

[22] Pian, 36.

[23] Each abbreviated character in jianzipu contains “fingering” and the string number of each note. Enclosed in the jianzi is a number, written larger than any other number in the quadrate that indicates the string on which to perform the movement. Above it is an abbreviated sign that describes the fingering on the hand used to stop the string and a number.

[24] The Songshi (Song history) of 1345, the standard history of the Northern and Southern Song dynasties, includes no formal biography of Jiang Kui as a man of letters a distinctive and complex artist. (Lam, 95)

[25] A formal biography in the dynastic histories is, by Chinese standards, the ultimate official recognition of an individual's literary or intellectual achievement and historical significance. That the Songshi does not give Jiang Kui a place among his literary contemporaries is obviously an oversight and a warning to the present-day reader of the biases and limitations of official Chinese histories and biographies: Jiang Kui is now recognized as a major poet in Chinese literature. The Songshi, nevertheless, preserves a long citation from Jiang's "Dayue yi" (Memorial on proper music) which was presented to the court in 1197 (Songshi, 131.3050-54). In other words, the Songshi gives a de facto recognition of Jiang Kui's musical talents and theoretical knowledge, and the memorial attests to the scholarly aspects of the artist's musical thought and composition. Jiang Kui's memorial attracted fourteenth-century Chinese historians and biographers because it discusses state sacrificial music, a unique genre that was an integral component of religious-political activities in historical courts of China. By recording and highlighting the memorial, the historians of the Songshi not only accepted the artist as a notable music theorist and composer, but also demonstrated their efforts to pay due attention to the Confucian ideology of proper music and its musicians. As claimed by Confucians, proper music is a counterpart of ritual, and serves as a means of governance and self-cultivation; only proper music is worthy of the scholar-officials' attention; popular music and its musicians, especially female ones, should banned. This is why in its commentaries on Jiang Kui's memorial, the Songshi makes a specific reference to the artist's composition of ritual songs, ten of which honor historical figures and extol the virtues they exemplify (Songshi, 131.3054).

Bibliography

Kang-i Sun Chang and Stephen Owen. The Cambridge history of Chinese literature. Cambridge, UK ; New York : Cambridge University Press, 2010. Print.

Xia Chengtao. Jiang Baishi ci bian nian jiao jiao. Shanghia: Shanghia gu ji chu ban she: Xia hua shu dian. 1998. Print.

Chang Ching-ho and Hans H. Frankel. Two Chinese treatises on calligraphy. New Haven: Yale University press. 1995. Print.

Rulan zhao pian. Song Dynasty Musical Sources and Their Interpretation. Harvard University Press, 1967. Print.

Lin, Shuen-fu. Voices of the Song Lyric in China. Berkeley: University of California, 1994. Print.

Lam, Joseph S. C.. “Writing Music Biographies of Historical East Asian Musicians: The Case of Jiang Kui (A.D. 1155-1221)”. The World of Music, 2001. Print.